Abstract

Introduction:

Pertussis, also known as “whooping cough,” is caused by the fastidious, gram-negative coccobacillus, Bordetella pertussis.[i] Before the introduction of pertussis vaccines in the 1940s, the disease was a major cause of childhood mortality. Although vaccination has significantly reduced incidence, recent declines in vaccine uptake have led to resurgences, underscoring the importance of early recognition, treatment, and prophylaxis to prevent outbreaks.

Case Description:

A 17-year-old previously healthy male came to the Internal Medicine-Pediatrics Outpatient Clinic with a persistent cough. He had been evaluated two weeks earlier at an urgent care center and diagnosed with Influenza B. Additional testing included Strep, COVID, Mycoplasma, and chest x-ray, all of which were negative. Despite treatment with oseltamivir, the patient’s cough progressed into severe paroxysms followed by post-tussive emesis. He last received the pertussis vaccine in 2018 at age 11.

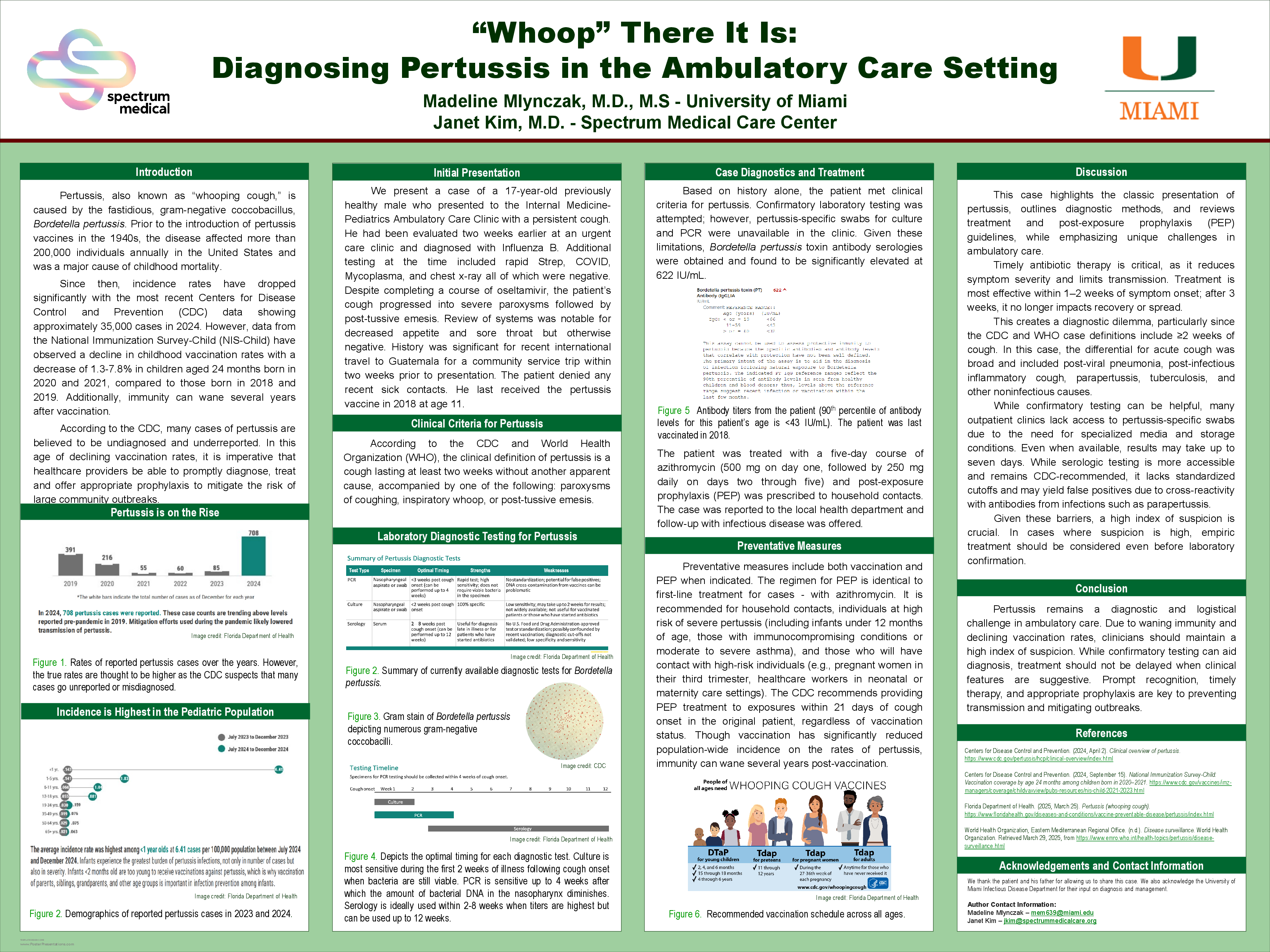

Based on history alone, the patient met the clinical criteria for pertussis. Confirmatory nasopharyngeal PCR and culture were unavailable, so B. pertussis toxin IgG serology was obtained and was significantly elevated at 622 IU/mL.The patient received a five-day course of azithromycin (500 mg on day one, followed by 250 mg daily on days two through five). The same regimen was prescribed for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to all household contacts.

Discussion:

Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO), the clinical definition of pertussis is a cough lasting at least two weeks without another apparent cause, accompanied by one of the following symptoms: paroxysms of coughing, inspiratory whoop, or post-tussive emesis.[ii] Diagnosis can be confirmed through laboratory tests, including culture; polymerase chain reaction (PCR); and serology. Both nasopharyngeal culture and PCR are recommended for use within 4 weeks following cough onset; however, the sensitivity of culture decreases after the first 2 weeks. Serology can be used up to 12 weeks after cough onset, but optimal antibody titers are typically seen between 2-8 weeks.

Timely antibiotic therapy is critical, as it reduces symptom severity and limits transmission. Treatment is most effective within 1–2 weeks of symptom onset; after 3 weeks, it no longer impacts recovery or spread. While confirmatory testing can aid diagnosis, treatment should not be delayed when clinical features are suggestive. Prompt recognition, timely therapy, and appropriate prophylaxis are key to preventing transmission and mitigating outbreaks.

[i] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, April 2). Clinical overview of pertussis.

https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

[ii] World Health Organization, Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office. (n.d.). Disease surveillance. World HealthOrganization. Retrieved March 29, 2025, from https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/pertussis/disease-surveillance.html