Abstract

Background: Learners cannot improve unless they know where improvement is necessary and how the improvements may be made (Mackway-Jones & Walker, 1998). At the same time people are notoriously bad at self-assessing their competence (Davis et al, 2006, Langendyk 2006) and recognizing their incompetence (Dunning et al, 2003). A concern is therefore that those who participate in simulation-training remain unaware of suboptimal behaviors. Debriefing may support abilities to assess performance but there is a lack of research on how debriefing supports observation skills. The aim of this study was to investigate course participants’ experiences of video-assisted debriefing and whether the debriefings supported them in observing good/suboptimal behaviors.

Research question: Do participants make more observations regarding the teams’ optimal/suboptimal performance before vs. after video-assisted debriefing? What are the participants’ expectations and concerns about the video-assisted debriefing and how do they view it as contributing to their learning?

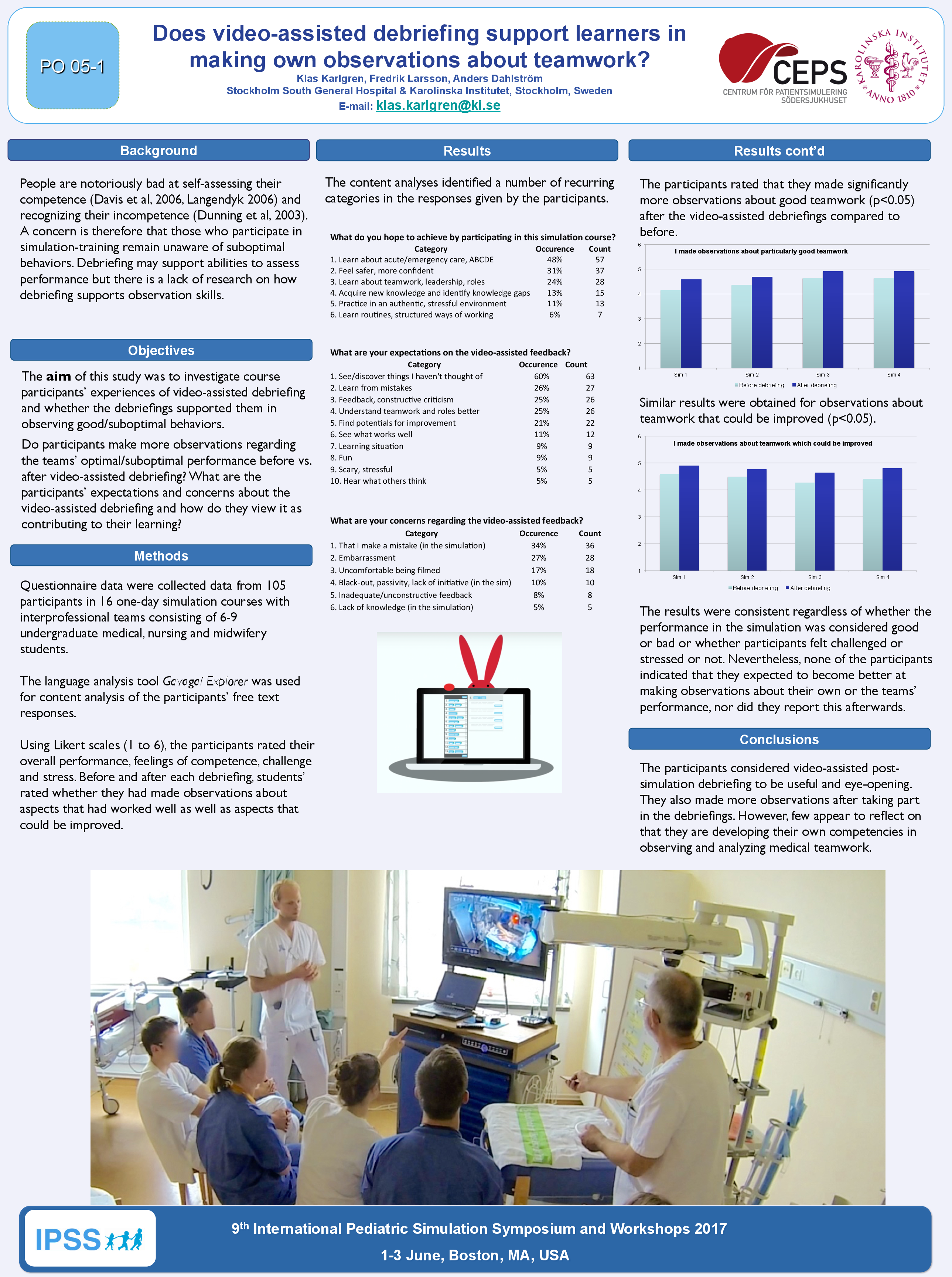

Methods: Data were collected data from 105 participants in 16 one-day simulation courses with interprofessional teams consisting of 6-9 undergraduate medical, nursing and midwifery students. Using Likert scales, the participants rated their overall performance, feelings of competence, challenge and stress. Before and after each debriefing, students’ rated whether they had made observations about aspects that had worked well as well as aspects that could be improved. A language analysis tool (Gavagai Explorer) was used to support content analysis on the participants’ free text responses in the questionnaires. The questions addressed what they were hoping to achieve, expectations and concerns regarding video-assisted feedback as well as how it contributed to learning.

Results: The participants expected to be given feedback about good and improvable aspects and although some had concerns about being filmed, they were positive and reported that they learned from the feedback. The participants’ rated that they had made significantly more observations about what had worked well (p<0.05) concerning teamwork after the debriefings compared to before the debriefings. Similar results were obtained for observations about what could be improved (p<0.05). The results were consistent regardless of whether the simulation performance was considered good or bad or whether participants felt challenged or stressed or not. Nevertheless, none of the participants indicated that they expected to become better at making observations about their own or the teams’ performance, nor did they report this afterwards.

Discussion/Conclusions: The participants considered video-assisted post-simulation debriefing to be very useful and eye-opening. They also made more observations after taking part in the debriefings. However, few appear to reflect on that they are developing their own competencies in observing and analyzing medical teamwork.